This week I am pleased to present Part II of a guest column by Jonathan Palmer about the burning of the steamship Henry Clay and a family from Oak Hill that perished as a result. Jonathan Palmer is the capable archivist at the Vedder Research Library in Coxsackie and Deputy Greene County Historian. At the conclusion of last week’s column, Palmer opines that many people buried in the Oak Hill Cemetery were pioneers of the nation’s new industrial frontier and the era to follow. He continues as follows.

Burning of the Henry Clay, Part II

It is a grievous irony therefore that this same social class would end up being the victims of one of the great tragedies of their time, and that this tragedy would be brought about by the invention that typified the age.

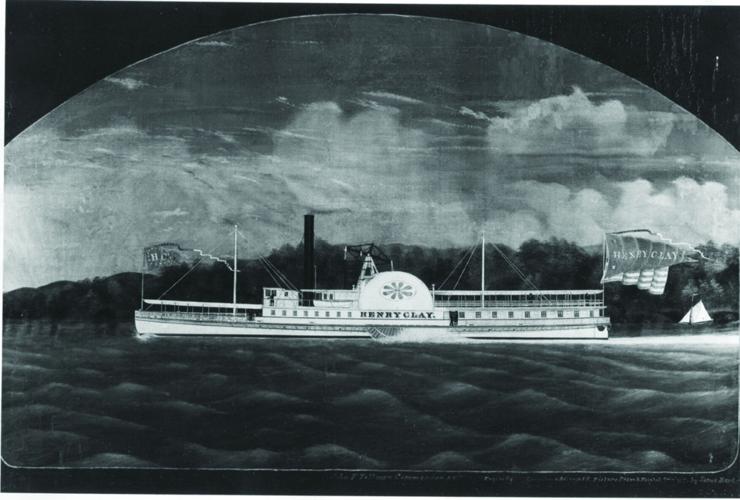

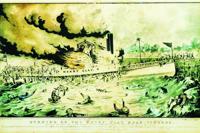

The Henry Clay and Armenia left Albany on the morning of July 28, 1852 racing neck-in-neck. These two ships were products of the same celebrated owner and builder (Thomas Collyer), a fact which only raised the stakes for the crews who knew victory or defeat would rest solely on their shoulders. Several hours into the race the Henry Clay held a comfortable lead of almost four miles over the Armenia, and such a distance could not be closed with the boats so near the finish line in New York. Just off Yonkers, as the Clay steamed towards victory, somebody on board noticed flames roaring up from the vicinity of the engine compartments. Efforts to suppress the fire were insufficient, and the fire quickly engulfed the midship. The vessel’s pilot made for shore and drove the Henry Clay at speed upon the banks of the Hudson where those near the bow could make good their escape. Unfortunately, those who found themselves trapped in the comfortable accommodations in the after section of the boat could not make their way forward to the shoreline and faced a terrifying choice between the approaching inferno and the roiling water below.

The class of passengers traveling on the Henry Clay that day was of a particularly affluent nature. On board were statesmen, judges, artists, authors, and relations of the great notables of the era. Andrew Jackson Downing, one of the 19th century’s most influential architects and a pioneer in landscape architecture and horticulture, was counted among the passengers. His charred remains would not be found until several days after the accident. The flames themselves a number of others, but drowning would take the lion’s share of victims. The ship’s paddle wheels didn’t stop turning in time for many who had chosen to leap from the aft section into the Hudson - the engines, out of control since flames had driven the engineers from their stations, washed victims in the water away from shore out into the channel. This continued until the boilers themselves succumbed, releasing a scalding breath of steam which killed others that the Hudson and approaching flames had so far spared.

It was in the water that the Ray and Cook families of Oak Hill hedged their bet. Mrs. Cook pleaded to her husband that he escape, and probably found small comfort in knowing her grandchildren at least made it to the water. At this point there is conflict in extant accounts, but by all indications Mr. and Mrs. Cook would end up surviving the calamity only to find that their daughter Abbe Ann, son-in-law William Ray, and granddaughter Caroline met their end in the water that had seemed sure salvation from the burning wreck. In the same newspaper which carried this tale of the Cook family’s tragedy the editor of the Greene County Whig ran a statement that he was hedging bets on the Alida as contender for the fastest and most reliable boat on the River, clearly oblivious to the tastelessness of the juxtaposition.

The burning of the Henry Clay, followed by a similar and equally tragic explosion on the Reindeer that September, sparked uproar at the management of the steam passenger and freight industry on the Hudson. Similar to the calamitous sinking of the Titanic sixty years later, the people most affected by the burning of the Henry Clay were of the same social class that thought themselves impervious to such tragedies by nature of their money, influence, and importance. Indeed, these people ended up reaping the bitter harvest of their industrial speculations and business practices, and it would be but a short time after the Rays were laid to rest at St. Paul’s that reformists would call for a reassessment of the industry - the silver lining to a tragedy whose victims were celebrities and notables.

The Ray family would never know it, but the accident which claimed their lives paved the way for a golden age of steamships on the Hudson. In the face of new regulations passed by Congress and the New York State Legislature operators found themselves incapable of running their companies in a fly-by-night manner. With the practice of racing outlawed the steamship industry grew into a safe and reliable operation which offered legitimate competition with rival rail lines in the Hudson Valley for nearly another eighty years. In the end this legendary industry would simply fall victim to the same technological innovation which had brought the steamboat to the forefront a century previously, relegating the Ray family to the footnotes in a story of bygone times.

Reach columnist David Dorpfeld at gchistorian@gmail.com or visit him on Facebook at “Greene County Historian.”

Johnson Newspapers 7.1