HUDSON — The 326 Warren St. pocket park was full Thursday night for a screening of Hudson-based filmmaker Theo Anthony’s film “All Light, Everywhere.”

The documentary investigates the history and modern-day use of cameras and surveillance, particularly police body cameras. Anthony worked on the film from the summer of 2016 until December 2020. It premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January.

Anthony began his interest in researching how power dynamics are changed with body cameras during the protests in Baltimore in response to Freddie Gray’s arrest and death, he said.

There is a lot of lip service about transparency and accountability when it comes to body cameras, Anthony said.

“That’s all fine and great but if you’re not actually setting the policies or enacting the changes that allow for accountability, you’re not really doing anything but wasting people’s time,” he said.

The film demonstrates that the cameras largely serve a purpose to protect police officers rather than the public and Anthony has been advocating for the county to develop its body camera policies to better serve the public.

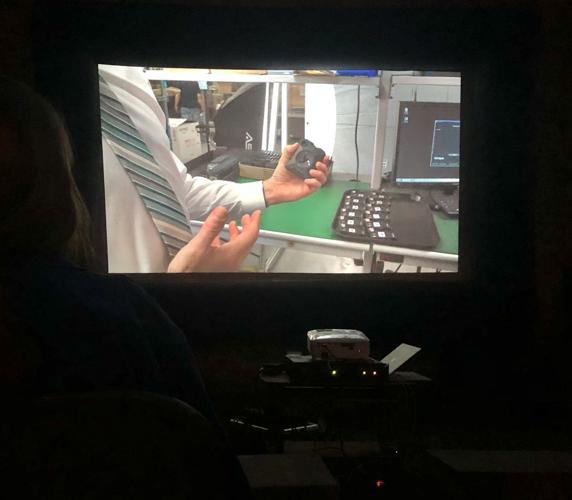

The filmmaker focuses on Axon body cameras, which the Hudson Police Department and sheriff’s department both use. Anthony’s film explored how the settings on the Axon cameras can present select perspectives of police incidents.

Viewers get a tour of the company’s facilities and get to sit in on an Axon training session for the Baltimore Police Department. Anthony, who lives in Hudson, is from Baltimore.

Anthony served on Hudson’s Police Advisory and Reconciliation Commission and spoke about the use of force and body cameras at a presentation in January that centered on the release of the committee’s 95-page advisory report. The Axon body cameras worn by Hudson police officers show what happens to officers but not necessarily the officers’ actions, he said at the January presentation.

Various political candidates spoke before the screening, wrapping up with 3rd Ward Supervisor Michael Chameides speaking about the film’s connection to local issues.

Chameides criticized the county’s decision to spend $500,000 on a five-year body camera contract, saying the decision was rushed and the money could have been used toward other important issues such as transportation or mental health services.

He expressed frustration over the county’s lack of body camera policy, saying the policy is a copy-paste version of the state recommended policy.

Chameides wrote a letter to the Columbia County Board of Supervisors on April 5 with eight body camera policy recommendations, which Anthony supports.

Anthony said that while the Hudson police department has been receptive to recommendations, he believes the sheriff’s office and county police reform implementation committee have not been taking them seriously.

Chameides has tried to bring Anthony in as a speaker for the committee, but to no avail, he said.

“The county is spending $100,000 a year on body cameras,” Chameides said on Friday. “But those cameras are only as effective as our policy. Fortunately for us, we have a local resident, Theo Anthony, who has been researching body cameras and body camera policy. Furthermore, through his work, he has other experts he can draw on. As the county creates its first-ever body camera policy, I’ve suggested we invite Mr. Anthony for a discussion with the implementation committee. Unfortunately, he has not been invited. It’s a missed opportunity and we aren’t taking advantage of our local resources and talent.”

Lt. John Rivero, the public information officer for the sheriff’s office, who he said also serves as a resource for the implementation committee, said Chameides’ recommendations are one of many topics on the committee’s agenda that members are discussing.

“We’re still in the beginning stages of discussions at the panel,” he said Friday.

Rivero said the department did not want the cameras to be sitting around unused, so a model policy from the state is being used as the implementation committee develops policies.

“We’re just kicking around different ideas and suggestions and everyone on the committee is contributing in their own way,” he said.

Rivero said the committee is not going to make policy based on one person’s recommendations and that it will take time to form policies as committee members do their own research. Some parts of Chameides’ recommendations may work and others may need to be tweaked, he said. Chameides has valid points but they need to be addressed and the committee has not come to a resolution yet, Rivero added.

“This isn’t something that’s going to get done overnight,” Rivero said.

Anthony expressed frustration over the committee’s conversations about body camera policies, wanting to bring in experts on the equipment that he worked with while making his film. Anthony drew a comparison between the committee’s discussions on the body cameras to someone buying an expensive television without reading the instruction manual.

“These are really nuanced, complicated technologies,” Anthony said.

Among Chameides’ recommendations to the committee is to expand the buffer mode of the camera recordings to include longer video as well as audio, Anthony said. This decision would not cost any money and helps ensure critical information is included, he said. But committee members discussed concerns about officers being afraid the cameras will record them in the bathroom, Anthony said. There are ways to redact and censor the footage to protect officers’ privacy, he added.

Overall, Anthony feels the people discussing the cameras do not fully understand them or all of their functions, and said many of the reform suggestions are just the matter of changing the preferences on the software.

Another policy focus for Anthony and Chameides is not allowing police officers to change their sworn statements after viewing body camera footage. They suggest a policy for officers to be able to add notes to their sworn statements after viewing the footage, instead of changing the initial statement. Anthony said the policy would be a good faith compromise.

Another recommendation is for the Sheriff’s department to not be allowed to manipulate video footage, such as cropping, zooming or changing the speed, Anthony said. It’s not police officers jobs to create a narrative, he added.

A lot of the funds for the cameras are coming from federal and state grants, but in the future the cost could be a significant burden on taxpayers, Anthony said, adding that the county should have a metric to evaluate if the technology is worth the cost.

“These are all so simple and you’d think it would be simple,” Anthony said. “You think it would be common sense. We’re not screaming at the top of our lungs to defund the police...” Anthony is concerned that body cameras in the county are used under the guise of police reform.

“I trust that there is a lot of smart people in the room that given the right information, we could have some serious action,” he said. “But what I’ve seen at the county level is a case study in how the language of equity and justice gets used as a cover for just the same-old, and I really wish, if we’re going to be having this conversation on police reform, then it requires more than asking the police to reform themselves. It defeats the purpose of the conversation. Essentially, it has to be a conversation and not a monologue.” While body cameras are bought to hold police accountable they often end up being used as devices to defend police, not the public, Anthony said.

“They only end up defending police perspectives and that is not the function of these devices,” he said. “On the county level I would love to see Sheriff Bartlett open up the conversation to real experts who know how these cameras work.”

Bartlett could not be reached for comment by press time.