CATSKILL – Corrections officers with the Greene County Sheriff’s Office violated state law and its own policies, which could have prevented the 2018 suicide of one inmate at the now-closed Greene County Jail, and authorities did not properly investigate the death of another, according to a December 2019 state report.

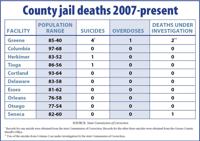

The jail, overseen by the Greene County Sheriff’s Office, had four suicides and one overdose in the last 12 years. Two of the deaths remain under investigation by the state Commission of Correction.

The original county jail, built in 1908 on Bridge Street in the village of Catskill, was closed April 20, 2018, following a Kaaterskill Associates analysis that revealed the south wall of the building was structurally compromised, or dangerous for inmates and staff.

Construction on a new 64-bed Greene County Jail, adjacent to the maximum security Coxsackie Correctional Facility on Route 9W, is expected to start accepting inmates in July 2021. The jail project is funded by a $39 million bond from Robert W. Baird & Co. Inc. at 2.49% interest and an $8.1 million contribution from county taxpayers.

Greene County Jail’s population peaked at 85 inmates in 2013, according to 2010-2019 Commission of Correction census records. Four suicides, with two under state investigation, and one overdose death in the last 12 years outpaces similar-sized jails in the state.

By comparison, Herkimer and Tioga county jails, which have population highs of 83 and 86, respectively, each reported one suicide in 12 years. Seneca County Jail, with a population high of 82, has one death under investigation.

Nine similarly sized county jails across the state reported zero overdoses in the last 12 years, according to data from those facilities.

MATTHEW LEOMBRUNO

The state Commission of Correction cited several failures in the Greene County Jail administrators’ response to warning signs inmate Matthew Leombruno might harm himself, according to a Dec. 17, 2019 report from the commission. The report was received Jan. 24 after a Freedom of Information Law request during a year-and-a-half investigation by The Daily Mail.

The state Commission of Correction ensures local jails comply with the state’s minimum standards, regulations and laws for the safety and well-being of inmates, staff and the community.

Corrections officers found Leombruno, 43, of Coxsackie, hanging from a bedsheet tied to the jail cell bars at about 11:30 p.m. on April 12, 2018 at the Bridge Street facility.

Leombruno died from his injuries at Columbia Memorial Hospital in Hudson two days later.

Greene County attorney Edward Kaplan denied The Daily Mail’s FOIL request Dec. 16, 2019, for the incident report of Leombruno’s death. Releasing the report would be an invasion of privacy and may deprive a person of a right to a fair trial or impartial adjudication, Kaplan wrote in his response.

The jail permanently closed eight days after Leombruno’s death. Greene County inmates were transferred to and are boarded at Albany, Ulster and Columbia county jails.

The state Commission of Correction released a report on Leombruno’s death last December following an investigation conducted by the state’s Medical Review Board.

Established within the commission in 1972, the board “investigate[s] deaths in correctional facilities within the state and to make recommendations for improving the delivery of health care to detainees and sentenced offenders,” according to the commission’s 2018 annual report.

The board determined jail administration violated state corrections law by failing to keep Leombruno safe. The law requires a jail’s chief administrative officer to “receive and safely keep in the county jail of his county each person lawfully committed to his custody.”

The state Commission of Correction cannot conduct a criminal investigation or press criminal charges. The commission can issue citations and directives to law enforcement, petition a court if the directives are not followed or close a jail facility, state Commission of Correction Public Information Officer Janine Kava said Nov. 15, 2019.

“The issue of should a criminal investigation be undertaken to determine what happened there is up to law enforcement,” Kava said.

Staff both failed to recognize Leombruno’s “serious suicidal ideation,” and failed to take proper safety precautions, including placing him on constant watch, which could have prevented his death, according to the report.

Corrections Sgt. Christopher Statham, whose name was redacted in the commission’s report, but was included in a subsequent civil lawsuit, violated several portions of the jail’s mental health policy. Statham did not put Leombruno on constant watch after receiving a phone call from his brother-in-law that Leombruno might harm himself, according to the report, which redacted his family members’ names. The names were included in the lawsuit.

Kaplan denied The Daily Mail’s Freedom of Information Law request July 7 for Statham’s disciplinary records due to the pending litigation.

Statham remains a county employee. The sergeant has been employed by the county since 2012, according to Empire Center records, earning $61,970 in 2019.

Statham “failed to identify the inmate risk factors which were listed in the policy such as, ‘manifests any increase of decrease in sleep, gives away personal belongings, actively discusses suicidal intent, manifests signs of serious mental illness such as hallucinations,’” the report stated.

The sergeant also did not place Leombruno on constant watch after listening to several statements of suicidal intent in recorded phone calls between Leombruno and his daughter, according to the report.

“The Medical Review Board finds this was also a violation of the policy which states: an inmate should be placed on a constant watch if the inmate recently verbalized suicidal intent or a family member communicates their knowledge of such intent,” according to the commission’s report.

The jail administration’s misconduct violated a state corrections law requiring the chief administrative officer or facility physician to determine when a prisoner requires additional supervision based on his or her condition, illness or injury. If warranted, the chief administrative officer must order the additional supervision under the law.

Leombruno was in jail on a felony theft charge after he was accused of fraudulently accessing and removing money from someone’s bank account without permission, according to state police. Investigators verified the theft at several bank ATMs, police said.

Leombruno was arrested April 5, 2018, in Athens and charged with third-degree unlawful possession of personal identification information and petty larceny, both class A misdemeanors; and fourth-degree grand larceny, a class E felony; according to the report.

Leombruno, an industrial pipe welder, had four children: Rebecca, 23; Damian, 15; Kaitlyn, 12; and Ryan, 6, according to his obituary, which was published in The Daily Mail on April 16, 2018.

A CIVIL SUIT

Leombruno’s family filed a $35 million civil lawsuit in federal court March 29, 2019, against Greene County and unnamed corrections officers at the jail alleging negligence and wrongful death following his 2018 suicide. The lawsuit is pending, with a deadline for discovery of evidence set for Aug. 31 and depositions are due by Dec. 31.

Family members said their warnings to the jail staff about Leombruno’s threats of suicide went unheeded, according to the suit.

Leombruno’s death was avoidable, his family’s attorney Mark Greenberg, of Greenberg & Greenberg in Hudson, argued in court documents.

“When prison authorities know or should know that a prisoner has suicidal tendencies or that a prisoner might physically harm himself, a duty arises to provide reasonable care to assure that such harm does not occur,” according to the suit.

Greenberg declined to comment, citing the pending litigation. The Leombruno family, through Greenberg, declined to comment.

During his incarceration, Leombruno made 132 phone calls, according to the state’s report, which redacted his family members’ names. The names were included in the lawsuit. Of the 132 calls, Leombruno spoke to his daughter, Rebecca, 18 times. It is unclear who Leombruno was trying to contact in the other calls.

The sheriff’s office recorded the calls.

Rebecca told her father during an April 10, 2018 call that she did not have enough money for his bail.

Leombruno replied, “I cannot do this,” the report stated. The prisoner added he had not slept since arriving at the jail.

Leombruno previously served time in Greene County Jail.

He was charged with petty larceny, a class A misdemeanor, March 1, 2017. He was charged with petty larceny Jan. 8, 2018, but was arraigned and released, according to Catskill police.

Leombruno was also charged June 27, 2012, with first-offense driving while intoxicated and operating a motor vehicle with a blood-alcohol content .08 of 1 percent, both unclassified misdemeanors, but was released to a third party, according to state police.

He was held in April 2018 on $10,000 cash bail or $20,000 bond, according to the state report. The amount was reduced to $1,000 after an April 10, 2018, appearance in Athens Town Court. Leombruno, who entered the jail April 5, 2018, with $2 in his pocket and an electronic benefit card, did not have enough money for bail.

He was scheduled to return to court May 3.

In addition to the stress of not making bail, Leombruno suffered from depression and opiate withdrawal, according to the civil lawsuit.

On April 12, 2018, the same day Leombruno hanged himself in his jail cell, Rebecca again told her father she could not raise enough money for his bail.

“Leombruno’s voice became broken at times during the call,” according to the report. “He stated to his daughter during the call, ‘Tell [redacted] to take care of the kids… I cannot do it… I am not going to do it... Hold onto the money and if the kids need something, get it… I am getting out of here one way or another… I am not staying here… it is not going to be good.’”

Rebecca told her father he was scaring her and that she was going to notify the jail of his comments and intentions of self-harm. Leombruno said he would deny his daughter’s claims about his mental health, according to the report.

Statham was on duty April 12, 2018, as watch commander for the jail that day, according to the lawsuit.

Statham received a call from David Douglas, Leombruno’s brother-in-law and Rebecca’s uncle, at about 7 p.m. that same day.

Douglas told Statham that Leombruno had repeatedly called Rebecca and threatened to hurt himself. Statham replied jail personnel would listen to any prior telephone calls Leombruno made that day and would take action, if appropriate, according to the lawsuit.

Statham instructed Corrections Officer Ashley Proper Acker, who was identified in the civil lawsuit, to listen to Leombruno’s phone calls from that same day, April 12, 2018, according to the state’s review of the incident.

In an interview with commission staff, Acker said she was concerned about Leombruno and informed Statham of the content of his telephone call, according to the report.

Statham also reviewed the phone calls. The sergeant stated that Leombruno discussed Greene County District Attorney Joseph Stanzione and bail money, according to the report.

“When asked if he recalled Leombruno stating that he was not going to spend another weekend in jail or that he gave away commissary items, Sgt. [Statham] stated that he did not recall that,” according to the report. “Sgt. [Statham] did state that he recalled the female [Rebecca] stating she was scared.”

Statham did not respond to multiple calls for comment. Statham’s attorney, Gregg Johnson, of Clifton Park, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In a written statement to the commission, Statham said he did not believe Leombruno was going to harm himself and the jail’s mental health staff did not need to be notified to immediately evaluate the inmate because Leombruno never indicated that he was going to kill himself, according to the report.

Statham believed Leombruno was looking forward to a visit with his son and was making arrangements for bail, Statham said.

“There were several indicators which made me feel that this inmate did not meet the criteria to be placed on a constant watch, so he was not placed on said watch,” according to Statham’s written statement included in the state’s investigation.

The indicator for an inmate to be placed on suicide watch is “if you feel there is a grave risk,” Statham said, according to the report.

Statham’s statement of a suicide watch indicator is not in the jail’s policy.

The first 72 hours of incarceration is the most critical time for inmates who are contemplating suicide, according to county jail documents regarding the facility’s mental health policies.

“An inmate should be placed on suicide watch if there is any indication that they are a danger to themselves or others,” according to the policy. “It is better to place an inmate on suicide watch and be wrong than not place them on the watch and the inmate commit suicide.”

There is no indication Statham followed up with Leombruno after reviewing the phone calls, according to the report.

Statham did not notify incoming officers during the shift change of the incidents regarding Leombruno’s phone calls or questions about his mental health, according to the report. The sergeant violated state corrections law by failing to communicate pertinent information regarding an inmate at risk for attempting suicide, according to the report.

An investigator with the sheriff’s office, whose name was redacted from the state report, listened to the phone calls between Leombruno and his daughter during the investigation conducted by the sheriff’s office immediately following the incident.

“Leombruno made several hints that he was going to kill himself,” according to the investigator’s review of the recordings.

In the civil suit, Leombruno’s family’s attorneys Greenberg and Eugene Nathanson, of the lawfirm of Eugene B. Nathanson in New York, New York, allege Statham received inadequate suicide prevention training.

“Any instruction on suicide prevention by a corrections officer was a small segment of a one-month ‘Basic Course for Corrections Officers,’ taken by [Statham] from May-June 2011,” according to the lawsuit.

“Greene County does not require its corrections officer to study or review the mental health policy and procedures regularly, does not require its corrections officers to certify that they have reviewed the mental health policy and procedure manual and provides no ongoing training or instruction related to suicide prevention,” according to the civil suit. “Greene County’s policy and practice is to assign inadequately trained corrections officers to prevent suicide among prisoners.”

Details of other recent deaths of Greene County Jail inmates coming Tuesday in part two of Behind Bars.