ALBANY — New York’s corrections officers union filed suit Monday to overturn a new state law that will restrict the use of solitary confinement to punish incarcerated people in the state’s prison system.

The state Correctional Officers & Police Benevolent Association filed a federal lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Albany on Monday against the state Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, Gov. Andrew Cuomo and DOCCS Acting Commissioner Anthony Annucci over the Humane Alternatives to Long-Term Solitary Confinement Act, commonly known as the HALT Act, on behalf of the state’s 18,000 correction officers.

“Once again, our elected leaders have failed us — our members didn’t sign up for this,” NYSCOPBA President Michael Powers said Monday outside the federal courthouse in Albany. “This New York state Legislature, Gov. Cuomo the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision have sided with the criminals and enacted countless policies to cater to individuals who can’t conform to society’s rules. I, for one, cannot stand by any longer.”

The HALT Act, which Gov. Cuomo signed into law March 31, prohibits incarcerated people in special populations from being sentenced to solitary confinement and limits their keep-lock placement to 48 hours. Prisoners cannot be placed in solitary confinement for more than 15 consecutive days, or 20 out of 60 days unless they commit specific acts.

The law redefines special populations to be excluded from solitary, such as pregnant women, or those with disabilities and significant mental health issues, and also mandates people in solitary confinement to receive programming by therapeutic staff five days per week.

HALT is set to go into effect April 1, 2022.

“While the department cannot comment on pending litigation, DOCCS has a zero tolerance policy with respect violence in our facilities and pursues both disciplinary charges and criminal prosecution for any assault,” DOCCS spokesman Thomas Mailey said in a statement Monday. “A new felony conviction would result in a consecutive sentence of imprisonment.

“The HALT bill has been signed into law and DOCCS has been working on a plan to safely implement the law, which still provides for segregated housing for acts of violence against officers and other incarcerated persons,” Mailey said.

Representatives with NYSCOPBA said the law is a fabrication concocted by advocacy groups and passed by a Legislature that disregard the lives and well-being of state correction officers and prison staff.

The state has 1,583 New Yorkers, or about 5% of its incarcerated population, housed in a Special Housing Unit as of Monday, Powers said.

An inmate physically beat and attempted to rape Correction Officer Chloe Hayes, a woman who works at Greene Correctional Facility, on June 5, 2020. Hayes, who returned to work last week for the first time since the attack, shared details of the incident outside the federal courthouse in Albany.

Hayes is named as a plaintiff in the union’s lawsuit.

Hayes recounted how the man cornered her in a closet and punched her in the face several times, ripped her shirt open, pushed against the wall and kneed to the floor.

“If it wasn’t for someone hearing my screams, I don’t know how this situation would have turned out,” Hayes said. “The act that was committed by this inmate has changed my life forever. He is protected for his unprovoked actions while my life has been interrupted.”

The man was placed in a SHU for 15 days as punishment, as determined by DOCCS.

“The Department has zero tolerance for violence and will pursue both disciplinary charges and criminal prosecution for the assault,” Mailey said. “A new felony conviction would result in a consecutive sentence of imprisonment. The disciplinary sanction issued to the incarcerated individual had him assigned to a Special Housing Unit for approximately six months and then transitioned to a Step Down Unit. These units, also known as residential rehabilitation units, prepare individuals for release back to general population.”

Hayes argued the HALT bill is designed to help the most violent incarcerated people and will be a detriment to prison staff, including officers, nurse, civilians, counselors and teachers.

“I ask the state of New York to reconsider this bill,” she said. “We want to know with all we do that we can go home, too.”

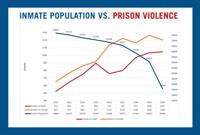

Assaults on corrections officers have nearly doubled over the last decade while the inmate population has decreased by about 20,000 people — a catalyst for the union’s challenge of the new law.

DOCCS reports 1,047 incidents in 2020 where an incarcerated person assaulted a correction officer with just under 34,500 New Yorkers imprisoned statewide last year, up from 524 assaults on staff in 2012 when the incarcerated population totaled 64,865 people.

DOCCS is at its lowest level in 37 years. The total incarcerated population in state correctional facilities is 31,417 people as of April 30 — a reduction of more than 24,560, or 44%, people since Gov. Cuomo took office Jan. 1, 2011, when the population totaled 55,979 incarcerated New Yorkers.

2012 and 2016 settlements between the New York Civil Liberties Union and DOCCS to overhaul state’s solitary system have required the state to have fewer isolating conditions, expand programming and eliminate using Special Housing Units as punishment for minor violations.

Powers argued the rulings watered down the state’s discipline system, which led to increased assaults between incarcerated people and corrections officers and among prisoners. The presence of contraband has also risen dramatically.

“DOCCS acknowledges that the limitations it has imposed on segregated confinement through the NYCLU settlement have effectively placed incarcerated individuals who pose a significant threat to the safety of others back into the general population of the facility, with direct access to [staff] who are attempting to do their jobs safely and incarcerated individuals attempting to serve their sentences peacefully,” according to the suit.

An incarcerated person is confined to a small cell in a Special Housing Unit

“Depending on the nature of the offense, the department uses a combination of both non-confinement and confinement sections to respond to misbehavior by incarcerated individuals,” Mailey said.

Powers argued incarcerated New Yorkers held in Special Housing Units receive amenities, such as increased phone access and calls compared to the general prison population, and visitation is permitted.

“Let’s be frank, solitary confinement doesn’t exist, in reality,” Powers said. “The concept that SHUs are these dark, dank holes in a basement somewhere are the furthest thing from the truth,” he said. “When you’re dealing with individuals that don’t subscribe or get along in the rehabilitation system, it’s no different than society. We have disruptions in society, we remove them from the streets. It’s no different inside a correction facility.”

Jerome Wright, a statewide organizer with the -HALTsolitary campaign, spent 30 years in medium and maximum-security prison for a murder he committed at the age of 18 in the late 70s. He was released in 2009 at the age of 48.

Wright spent nearly eight years in solitary confinement over three decades in 18 facilities across the state, including in the north country and downstate.

His longest stint in the SHU was two and-a-half-years.

“Many people don’t make it out of there,” Wright said. “Everyone who makes it out of there does not come out unscathed.

“They’re giving some draconian pitch of what solitary is ... as if I was looking for an Oscar — I’m trying to save Oscar’s life. ... Solitary is isolation and it is torture. It is torture of the first order.”

Wright was housed in solitary confinement in several prisons, including at Wende, Auburn, Attica, Elmira, Green Haven and Southport correctional facilities.

He served two and a half of a seven-year sentence in solitary confinement after his involvement in a violent incident at Wende Correctional Facility in Buffalo. Other inmates assaulted Wright after he testified in Santiago v. Miles — the federal 1990 civil rights case to fight discrimination at Elmira Correctional Facility.

“I was tortured; for them to say you get all of these special privileges, that is a bold-faced lie,” Wright said. “People do not receive multiple phone calls ... there’s no one coming to these units, there’s no staff coming to these units. The guards who were there barely walk on the units. This is not hyperbole. I lived this, and thousands of people didn’t make it out of there.”

Corrections officers would not be filing a lawsuit to prevent the Halt Act if people housed in the SHU are provided with adequate phone calls, visits with loved ones and other amenities, Wright argued.

“There’s no reason you should be keeping people in a 6-by-9 cell for weeks, months, years or decades and expect them to come out of that environment better. We treat people like animals, and then when they act like animals, we’re surprised. We experimented with punishing people enough. Let’s experiment with rehabilitating people.”