Pamela Salisbury Gallery: Seth Becker’s Terrarium and Lisa Corinne Davis’s All Shook Up. Excerpts from Wilkin’s “At the Galleries” in The Hudson Review follow below.

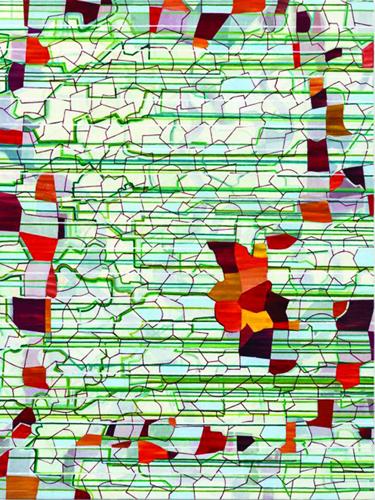

Seth Becker, Scene from the Hall of Ocean Life, 2020, oil on panel, 12 x 9 inches

In the Carriage House of Pamela Salisbury Gallery, “Seth Becker: Terrarium” presented intimate, intense, lushly painted images that at first seemed to be straightforward, casual, firmly structured records of perception, but soon became stranger and stranger. We stared down at a box of sardines, angled a little against the rectangle of the support, then discovered that we were offered the same viewpoint of Becker’s small black dog barking at his shadow. Both paintings were noteworthy for their pale, earthy hues, assured brushmarks, and deadpan subject matter. The piled fish and the dog’s open-mouthed shadow became immensely important. So, in other works, did the contrasting paint colors and doorframes on each half of an attached house and a spray of fireflies hovering in front of a corner building.

Still other works took as their point of departure the Museum of Natural History, whose illusionistic diorama backgrounds were, we learn, the first paintings Becker encountered as a child. “They formed the documentary nature of how I see,” he writes in a text accompanying the exhibition, “and instilled a sense of wonder at the phenomenal world.” Among the most mysterious paintings in the show was the moodily lit Scene from the Hall of Ocean Life, 2020: a large, pinkish, near-spherical fish, hung high above the pier of an archway, casting a round shadow on tawny stone; against the pier, a minimally indicated, abruptly cropped figure. We were denied a place to stand, forced, instead, to con-front the suspended fish and its shadow, and to consider the relation of those circular shapes to the curves of the archway, just as we confronted the sardines and considered their box in relation to the rectangle of the panel. Throughout “Terrarium,” we were made to concentrate on things that we would otherwise fail to notice or to think of as significant. Perhaps spending time with Becker’s work could sharpen our perceptions.

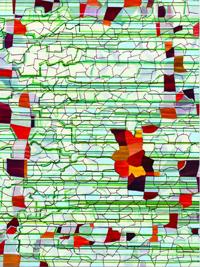

Flitting Foundation, 2019

Lisa Corinne Davis, Flitting Foundation, 2019, oil on canvas, 40 x 30 inches

Yet another approach to relevant subject matter could be seen Upstate, at Pamela Salisbury Gallery, in Hudson, N.Y., where the accomplished, disconcerting abstractions in “Lisa Corinne Davis: All Shook Up” explored, we learned, “themes of racial, social, and psychological identity.” Some years ago, in an essay, “Towards a more fluid definition of Blackness,” published in the online magazine artcritical, Davis wrote, “Many African-American artists feel the obligation to represent Blackness. My position as an abstract painter allows me to manifest my own sense of self—my black self—as an expression of self-determination and freedom, while avoiding an oppositional stance.” Self-determined and free as Davis obviously is, as an admired artist with a distinguished career, represented in significant public and private collections, currently Head of Painting at Hunter College, her paintings seem to be about contingency (among other things), which could be read as a distillation of the instability of perception and the inequalities of the society we live in. Or not. Whatever motivation we assigned to them, her complex, layered abstractions in Hudson, made between 2017 and 2020, with their warped grids, luminous hues, and syncopated rhythms, kept us off-balance, provoking often contradictory associations, from the natural to the man-made, the ephemeral to the mechanical, the organic to the technological, all of it, perhaps, visual, wordless equivalents for how we see each other and how we see ourselves. Davis superimposes tangled, knotted, irregular grids of different kinds—delicate and coarse, angular and curvilinear, frayed and continuous, suave and staccato—punctuating them with nodes of more intense hues, now widely dispersed, now rhythmic, now dense. We shifted between seeing a pulsing whole and focusing—or trying to focus—on individual layers, then followed the irregular path suggested by the scattered solid fragments, always aware of how the grids, even the most geometric, refused to respond to the vertical and horizontal edges of the support. The result? Even more animation and invigorating tension. And, no matter what else the paintings triggered in us, we also capitulated to the seductive rhythms of the grids and patches, the sense of light, and the clear, fresh color.

In some works, such as Flitting Foundation, with its disjunctive lavender and green drawing, throbbing zones of pale blue, and implications of overlapping, the layers suggested fictive depths, as if we were staring into moving water, while the dramatic scale shifts in the vertiginous Illusive Index suggested the built environment, seen from a distance. The exhibition included large and small canvases and works on paper, all ringing changes on related themes. Whatever the size or material, they were unignorable and powerful. I was specially captivated by Deceptive Dimension, 2020, a small, lively canvas in which an unstable checkerboard of white and intensely colored not-quite squares hovers over a fragile web of short, slender lines and patches of paler hues; it was impossible to decide what was on top of what, which kept me fascinated and a little uncomfortable—a remarkably satisfying combination, as it turned out.